Last October J & I visited New York for (nearly) a week, mostly to see the Egyptian stuff in the Metropolitan Museum of Art – but we did do other sightseeing too 🙂 In terms of Ancient Egyptian stuff seen we spent two and a half days in the Met (including time in their exhibition on the Middle Kingdom that opened while we were there), and a day in the Brooklyn Museum. And for non-Egyptian stuff we managed to cram 2 tall buildings, a boat ride past a statue, Central Park (more than once, both walking & running), 2 art galleries & the Natural History Museum and a lot of tasty food & drink, into about a day & two half days. It was the sort of holiday you come back from feeling like you need a week on the beach to decompress before doing anything else … so instead we went away for a weekend in London with friends (and study days for J) before returning to reality with a bump!

A selection of my photos from the trip are up on flickr, here (or click on any of the photos on this post to go to it on flickr). There’ll be more Ancient Egyptian related ones later, but this set has all the sightseeing ones in it.

Day 0

Our journey out seemed to take forever, partly coz we stayed over in a hotel at the airport the night before our flight. But it was uneventful, and eventually we made it to the hotel. When we were booking pretty much every hotel in Manhattan, and particularly in the area near the museums, had reviews that talked about how small the rooms all were so we were kinda fearing the worst, but it was actually a pretty reasonable room and much bigger than we were expecting 🙂

Day 1

Our original plan was to do city sightseeing on the first day, but the weather forecast said that it was going to turn into the only bad weather day of the trip so we changed things around. We had to pick up the sightseeing passes I’d bought so we walked from the hotel through Central Park to do that, via a breakfast of pancakes and bacon (surprisingly tasty) in a diner along the way.

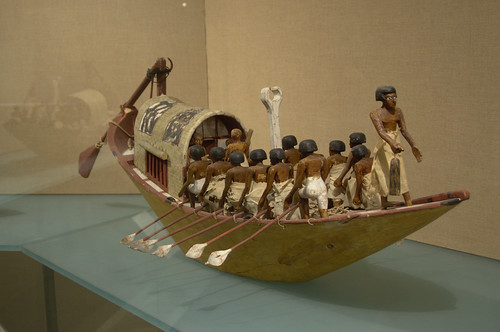

We then spent about 9.5 hours in the Met, and saw a bit more than half of their Egyptian things … I hadn’t actually realised quite how much stuff there was in there. We did pause for lunch btw, and were impressed with the cafeteria they had – loads of proper food options as well as sandwiches. Actually I quite liked the museum as a whole – even though we didn’t explore much past the Ancient Egyptian stuff, there was a lot there to see and we could’ve spent a lot longer than the time we had on this trip. The only annoying thing about it was in the Egyptian sections there were constant tours coming through that were purporting to tell their victims all about Egypt in the Bible. But sadly almost everything one overheard them say was utter bobbins – for instance the scarab beetle hieroglyph has nowt to do with the god Ptah, and the plague of locusts wasn’t sent to make Egyptians worry about taking the name of Ptah in vain as they spat locusts out. It wasn’t just wrong, it was fractally wrong – every statement I heard had me wondering where to start in deciding what was wrong with it. And as we spent a lot of time there, I had a chance to hear these stories multiple times …

Anyway, moving back to the interesting and non-tooth grinding stuff 🙂 The Egyptian galleries are laid out in chronological order and on this first day we managed to get from the prehistoric stuff through to the middle of the 18th Dynasty. I’m going to write up a bigger post about the Met once I’ve got all my photos from there online, so this post will only have general thoughts. One thing that struck me was that there was a subtle difference in how the objects were presented – the Met (and the Brooklyn Museum) are art museums rather than history museums. And although I can’t quite put my finger on how the presentation was different it did feel a bit more like the history was there to contextualise the object one was looking at, rather than the object being there to illustrate the history one was learning.

Day 2

For our second day we spent half the day doing sight-seeing before returning to the Met for the early evening (to take advantage of the late closing day). We started by getting up very briskly to try and beat the rush to the Empire State Building – which we pretty much did, still a lot of people but we didn’t have to queue terribly long.

After looking at Manhattan from on high, we next went to look at it from the water … We’d decided not to actually visit the Statue of Liberty, instead we took the Staten Island Ferry which goes past the Statue and gives you a pretty good view of it and of the iconic Manhattan skyline from below. We had our lunch over on Staten Island – we tried to strike off into the island itself to see if we could find somewhere to eat, but I think we went the wrong way and ended up in a distinctly Not Touristy part so after a bit of a failure of nerve we returned to the ferry terminal and went to one of the restaurants there. Despite it feeling like a bit of a cop out, we actually had a rather nice lunch and the service was possibly the best of the whole trip. We then took the ferry back – having taken lots of photos on the way out I just admired the view on the way back 🙂

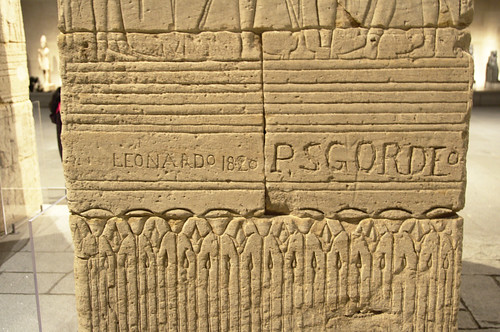

And then back to the Met – we got round almost all the rest of the Egyptian stuff, except for one suite of galleries that they randomly closed just as we were about to look at it (I think they didn’t have enough staff that evening? it wasn’t clear what was going on). We even got to the pièce de résistance today – a whole (small) temple. I really liked how they had the room it’s in laid out – the temple is surrounded by a moat, with a small handful of carefully chosen pieces of sculpture. One of the walls of the room is glass (from Central Park it looks like a glass pyramid), and so the temple is mostly lit by natural light during the daytime. And looking at the temple I even found some graffiti – that’s how you can tell it’s a real temple 😉 Mostly 19th Century European stuff, but I think some demotic as well.

Day 3

This was the only day of the trip that we left Manhattan – to spend all day in another museum full of Ancient Egyptian artifacts! We got to Brooklyn a little earlier than the museum opened, so did have a little wander about and a coffee in a nearby cafe. But the rest of the day was spent in the museum 🙂 They don’t have anything like as much stuff as the Met but there was still a lot there.

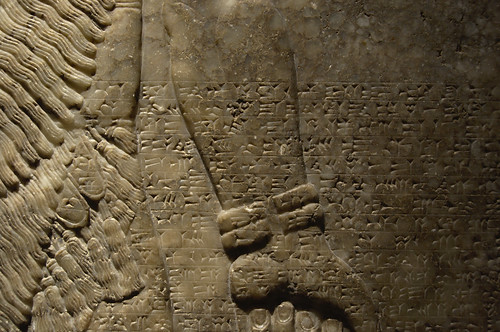

I did manage to fit in a look at their Ancient Near East room as well – I was amused to see that among their objects they have some of the same series of reliefs from Ashurbanipal’s palace at Nineveh as are in the British Museum. Apparently there were so many found that the BM sold some of them off as they simply didn’t have space to display or store them all.

Day 4

After a full day of museuming we spent the next day doing more city sightseeing. For someone who’s not keen on heights I was spending a lot of this holiday up tall buildings: we bookended this day with two trips up to the Top of the Rock, so that we could see the views in daylight and after dark. The trip up the Empire State Building was in large part because J felt you can’t visit New York without going up the Empire State Building … and the trip up to the Top of the Rock was because we wanted to see the Empire State Building in the skyline. And we also got a much better view of Central Park than we had from the Empire State Building.

After the first trip up a tall building of the day we headed to the Museum of Modern Art. I’d thought in advance that there might not be much there to my tastes – I’m not overly keen on “modern art” as a broad category. But it turned out that there were quite a few things I did like. There was plenty of stuff by Van Gogh, the Jackson Pollack pieces were much better in person than on the telly. I also liked the Rothkos, and several other things. And the Monet waterlily paintings … which wasn’t a surprise, I’ve always been fond of them 🙂 And other things too. But I still don’t like Picasso very much, and that’s who always pops to mind first when you say “modern art”.

We also looked at some of the contemporary stuff in MOMA, but that mostly just reminded us that the passage of time is a useful way of filtering out the good stuff from the dross 😉 After that we walked up to the Natural History Museum … hoping to find lunch on the way, but somehow I’d picked the wrong street for us to walk along as we didn’t see a single cafe or restaurant till we were right next to the museum. Still, we got to eat in the end 🙂 And then we saw dinosaur bones 😀 And some mammals, and early vetebrates. To be honest, whilst I was pleased we went to this museum, it felt much more like a commercial enterprise than any of the other museums – organised primarily to separate you (and any children you might have) from your money. But still, dinosaurs!

And then we walked once more. Back down towards Top of the Rock to while away the time till the sun set. We popped into Central Park on the way past to see the memorial to John Lennon. And then walked down Broadway for a bit, and had a drink in a bar around there. Once it got dark we headed to Times Square to walk through there (so, so, so tacky, but a box we felt we should tick), before going back up the Top of the Rock. We’d been pleasantly surprised at the speed the queues moved in the morning, but the evening showed us we’d just timed it right. The view was pretty good tho – worth queuing for! The Empire State Building was lit up in the colours of the Italian flag for the evening – because it was Columbus Day, and the New York Italians have a parade that day (we managed to not find out about it till later in the day, tho we had seen the barriers earlier and wondered what it was about).

Day 5

This was our last full day in New York, so obviously we spent it in the Met with the Egyptian stuff again! We did also pop into a couple of the other galleries – I wanted to see the Monet paintings they had, having seen the ones in MOMA and been reminded how much I like them. (I also bought a waterlily painting t-shirt as a souvenir!) In terms of Egyptian stuff we finished off the few rooms we hadn’t had a chance to see when they shut them on our last visit, but the main reason we’d gone there on that particular day was to see the special exhibition that had just opened about the Middle Kingdom. It was actually a surprisingly big exhibition – the Met is a huge space, and so what had looked like a medium size room on the floorplan turned out to be much bigger. The exhibition looked at how the art and iconography of Egypt was transformed during the Middle Kingdom period. The best known Pharaohs these days are from the New Kingdom (e.g. Tutankhamun, Ramesses II) or the Old Kingdom (e.g. Khufu and his Great Pyramid), but to the (later) Egyptians themselves the Middle Kingdom was their classical golden age. I plan to write up a more detailed post about it later 🙂

Day 6

We didn’t need to leave for the airport until mid-afternoon, so had a little bit of time on our last day to do a bit more touristy stuff. This was our opportunity to fit in a run round Central Park – we did a 6 mile loop at my speed (so slow for J) which was rather fun. There are an astonishing number of runners in New York, particularly in Central Park itself (which is also well set up for runners & cyclists with designated paths for them). And then after packing and checking out of the hotel we still had more time to kill so we popped into the Guggenheim Museum using up the last visit on our Explorer Passes. If we hadn’t been looking for something relatively near the hotel I don’t think we’d’ve visited this – it hadn’t sounded to our tastes, and turned out to be even less so than anticipated. Most of the galleries were closed because they were installing exhibitions, so the majority of what was visitable was an exhibition of work by Alberto Burri who was a 20th Century Italian who made paintings that were generally only one colour and the canvas would also have bits of plastic on it or holes in it to create texture. One, in isolation, might’ve been quite striking – there were one or two of the black ones that I almost liked. But fifty, laid out up a spiralling gallery, one after another after another, grouped chronologically (and thus all reasonably similar to their immediate neighbours) got rather relentless. There was also a small gallery open with some of their permanent collection which was more to my tastes – more like the range I’d liked in MOMA. Including a Picasso I actually liked!

And then it was time to go home – it had been a good holiday. I’d been ambivalent in advance, I’d been underwhelmed on my first short visit over 20 years ago, plus a lot of what people talk about when they talk about New York is shopping (which I wasn’t interested in) and there’s a distinct lack of medieval or early modern architecture (being as the city didn’t exist back then) which is often what I want to see when I’m sight-seeing somewhere. But I did enjoy it, although I think it may be a once-(properly)-and-done city for me 🙂