Towards the end of June J and I spent a day and a bit in Leicester. We headed across on the Friday evening, arriving with enough time for a leisurely dinner but not really time to do anything else. On the Saturday J was busy for the whole of the day with a study day about Egyptian mummies, held in the New Walk Museum, so I visited a few of the sights on my own. And took photos! The whole album is on flickr and several of them are in this post. Click the images to go to flickr for a larger view.

New Walk

The “New Walk” is a 200 year old pedestrian street which they seem very proud of – and it is rather pleasant to walk along and photograph!

I was amused by the Dominicans and their glossing over of that whole little Reformation thing in their claim to’ve been here continuously since 1247 … I mean, perhaps there were Dominicans continuously through the years it was illegal to be Catholic, but it feels more likely that they missed a year or two here & there 😉 The statue at the end of the walk, near the council offices, was of John Biggs – the name meant nothing to me, so I’ve had a look online and I’m only slightly the wiser. He was MP for Leicester in the 19th Century, and it appears he was a radical and a Non-conformist. But other than that I didn’t find much about him (with a rather cursory search – but there’s no wikipedia page for him, for instance).

Leicester Cathedral

The cathedral was in somewhat of a state of disarray when I visited – the outside area was being refurbished as part of the general facelift of the surrounding streets to accompany the new Richard III Visitor Centre (I managed to visit a month before that opened). And inside was being set up for the ordination of priests that afternoon, so there were chairs and labels and so on everywhere and people bustling about.

The inside of the cathedral felt in some ways quite Victorian or early 20th Century – the stained glass and the internal decor, I mean. But there are bits that are considerably older – according to the leaflet I picked up the nave is mostly 13th Century (bits early, bits late). And there are other parts that are 15th Century.

The church is dedicated to St. Martin, so one window shows the basic story of the saint (meets a beggar who is actually Christ, gives him part of his cloak).

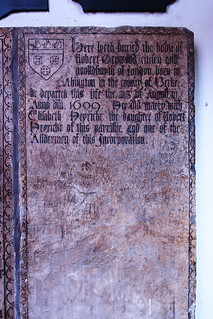

There are some rather old memorials – including some from the Civil War era. I was also rather amused by the more modern sign up in the side chapel dedicated to St Katharine – it contains memorials to the Herrick family, and was “made fit for divine service” by members of the family from the US in 1929. Which does make one wonder what state it was in before!

Richard III

Obviously everyone who hasn’t been living under a rock for the last couple of years knows that Richard III’s body was discovered by an archaeological excavation of a council car park in Leicester in 2012. I managed to visit Leicester at precisely the wrong time to see any of the exhibits relating to that! I was visiting a month before the posh new visitor centre was opened, and the temporary exhibition in the Guildhall was closed (presumably the stuff was being properly set up in the new exhibition space). All that was on offer was a statue outside the cathedral, a memorial stone inside and the reconstruction of his face in the Guildhall.

The Guildhall

The earliest bits of the Guildhall in Leicester date back to the late 14th Century, with most of it dating to the 15th Century. It used to be the place where the City Corporation met, and where the Mayor and the Town Recorder did their thing. It was also a place where theatrical performances were held during the 17th Century – and quite possibly Shakespeare performed there. Records definitely do show that a company he was part of performed there – the Earl of Leicester’s Men. And it’s also known that Richard Burbage (leading man for whom many of Shakespeare’s central parts were written, including Hamlet) performed there. So it seems reasonable to assume that Shakespeare was involved somewhere along the line. These days I think it’s just a museum, although I believe you can still get married there if you so wish.

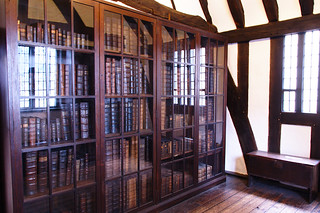

All in all it fitted in rather well with the various Future Learn courses I’ve done this year – two Shakespeare ones, an English Literature one (which included some Shakespeare) and a history course on 15th Century England (run by Leicester Uni, using Richard III as the jumping off point). So I spent a while looking around and taking photos. I particularly liked the coats of arms of various of the monarchs over the years (mostly in the Mayor’s Parlour). Upstairs they also had a room kitted out as it would’ve been for the Town Recorder to lodge there whilst doing his duties – quite bare bones really. The rest of the upstairs is a library (in the sense of “room of books” not in the sense of “lending library”).

Jewry Wall and Jewry Wall Museum

I had a quick look around online before we went to Leicester to see what there was to see, and saw that one of the tourist attractions was the Jewry Wall Museum next to the Jewry Wall. And was much puzzled by the name – I didn’t have strong associations between Leicester and Jews, but of course that could just be my ignorance. As it turns out, the name is nothing to do with the Jews. It’s a corruption of Jury Wall, and only began to be spelt that way in the 19th Century. And the wall itself is the only remaining section standing of the old Roman baths (which have since been excavated). For centuries after the Romans left it was used by the townsfolk as the landmark by which the town jurats (or elders) met, hence the name that developed. Or so said the signs in the Jewry Wall Museum – looking it up on wikipedia just now to double check it seems there’s some doubt about that (or wikipedia would like there to be, always hard to tell).

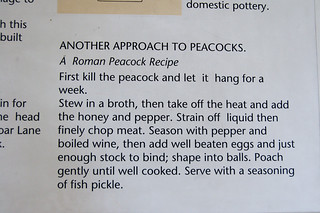

The Jewry Wall Museum houses material that’s related to Leicester’s past – mostly from Roman to Medieval times. It’s a curious mix of old-fashioned and very new – I believe it’s been kept open by volunteers and donations, so not much chance for systematic modernisation. It’s also quite a small museum. I rather liked it, there were several interesting items and they also devoted a reasonable amount of space to talking about archaeological methods and how they’ve developed over the centuries since the Enlightenment. I was particularly impressed with their selection of Roman wall paintings, all found locally.

New Walk Museum

My final museum of the day was the New Walk Museum. I was actually getting a bit museumed out by this stage – but I only had about an hour to kill before J was done with his study day, and he was in this museum so it seemed the sensible place to hang out and wait for him. I walked round most of the museum but didn’t take that many pictures. I’m not quite sure what the thematic statement for this museum was as it contained a pretty diverse mixture of things. There was an Egyptian collection, a set of dinosaur (+ friends) bones, a room aimed at children themed around sight and colour vision, a gallery of Picasso ceramics, a gallery about naturalists, a room with a Sikh fortress turban in, a room with a variety of objects organised by what they were made of and how they were made plus an art gallery which had a children’s play area in the middle of it. The overall impression was this was a space full of “stuff we have at hand”!

All in all a good day out, lots of interesting stuff seen. I do want to go back at some point to see whatever they’ve done with the new Visitor Centre for Richard III (and perhaps in a bit they’ll’ve finished digging up all the streets in the city centre which does rather spoil the look of the place as you wander about!).