The second episode of Helen Castor’s She Wolves: England’s Early Queens was about Isabella of France & Margaret of Anjou. Neither of these women ruled England in their own right, but both ruled in the name of a man (son & husband respectively) and neither have been remembered kindly by history. Rather unfairly, I think (although Isabella brought it on herself to some degree).

Isabella was the daughter of the King of France & was married to Edward II when she was only 12 years old. The marriage didn’t get off to an auspicious start when Edward sat his favourite, Piers Gaveston, closer to Edward at the feast than Isabella was and they ignored her to concentrate on each other. Even at this young age Isabella was very aware of the respect due to herself as a daughter of a King and a Queen herself. However, despite the fact that Edward was besotted with his favourite, Isabella set out to behave like the perfect Queen & wife.

Gaveston’s behaviour and indulgence by the King wasn’t just annoying & insulting to Isabella, it also wasn’t going down well with the nobles at court. Eventually the situation deteriorated to the point where the barons took up arms against Edward & his favourite, and they had to flee – with Isabella in tow. The situation was only resolved with the capture & execution of Gaveston. Relations between Isabella & Edward must’ve got better after this – if nothing else they started having children including the future Edward III. Isabella had therefore performed one of the critical duties of a Queen in ensuring the succession, she also played the Queenly role of peacemaker in mediating between Edward & the rebel barons.

However she was to play a critical role in the re-emergence of hostilities. She was travelling with her household when they were caught in a storm, and sought shelter at Leeds Castle (in Kent). The Lord of the castle had been one of the rebels but he was away, and his wife refused Isabella entry. Isabella was furious and ordered her men to force their way in, at which point the soldiers in Leeds Castle fought back (as you would) and six of Isabella’s men died. Edward called this insult to his Queen treason & used it as an excuse to beseige the castle, eventually capturing it & imprisoning the lady & her children. The lady’s husband was executed. I’ve got chronology muddled a bit here (I don’t think Castor did tho) and by this stage Edward II had already taken up with his next poor idea for a favourite – Hugh Despenser. Castor characterised Despenser as a political predator (and we got nice visuals of a raptor of some sort flying about and tearing at some sort of prey). She also said that she believes that relationship to’ve been platonic, unlike the one with Gaveston.

So now relations between Edward & the country are deteriorating & so are those between Edward & Isabella. Tensions are rising between England & France, too. Isabella seizes her chance when her brother (now King of France) wants to negotiate a peace – she volunteers to go to France to negotiate on England’s behalf. Once in Paris she organises for her son Edward to join her, and instead of returning to England as a dutiful wife she returns at the head of an army, fighting to depose Edward II & set Edward III in his place. She’s practically welcomed in, Edward II’s reign had become tyrannical and unpopular. Once Edward II was captured Edward III was crowned & Isabella ruled as his regent. Edward II subsequently died, almost certainly at Isabella’s orders (but not via the red hot poker of later myth). Isabella was widely regarded as the saviour of England at the time.

But she’d already sown the seeds of her downfall. Whilst in Paris she’d also taken up with a knight called Roger Mortimer (Castor made a lot of use of chess metaphors in this programme, in particular referring to the Queen making her move with her Knight & Pawn (Edward III)). So when she started to rule as regent she had her own favourite by her side, not quite what the nobles wanted to see. And she had always been very aware of her own majesty, and this only got worse when she was running the country – she and Mortimer enriched themselves at the Crown’s expense. So in the end Isabella was overthrown in her turn, by her son. Mortimer was executed, but Isabella was allowed to live on.

(Isabella is one of the viewpoint characters in “Iron King” by Maurice Druon that I read earlier this year, it’s set around the time of Edward III’s birth. Druon has her & Mortimer (very much pre any relationship) conspiring to catch her sisters in the act of adultery, oh the irony.)

The second half of the programme was devoted to Margaret of Anjou – the French bride of Henry VI. Henry had been King since he was 9 months old, when his father Henry V died. Unfortunately at the time Margaret of Anjou married him he still wasn’t showing much signs of capability to rule – he was 23 by then. And it got worse – Margaret became pregnant, but shortly before the baby was born Henry slipped into a catatonic state. The court was already divided into factions – one centred round the Duke of York (who had his own claim to the throne), one centred round the Duke of Somerset (who was pro-Henry). Castor was telling us that Margaret would’ve prefered that she was named regent – she felt she had the right as the King’s wife & that she was a more neutral choice than the other two. However it was the Duke of York who got the job. This is where the Wars of the Roses begin to properly kick off.

Henry did recover his wits (such as they ever had been), so the Duke of York was no longer regent. However relations between the Yorkist & Lancastrians had deteriorated to the point where civil war broke out. Margaret was firmly in the Lancastrian camp, keen to protect her husband & son’s right to the throne. Henry was fought over & captured/released and generally passed around like pass the parcel. Castor told us of the king sitting in the centre of St Albans, guarded by soldiers, while the fighting raged through the town – not participating, just bewildered as he was fought over. In the end York won, not to control the king but to rule in his own name. (By this stage it’s not the original Duke of York, it’s his son Edward who ruled as Edward IV.) Margaret & her son (and husband? I can’t remember where Castor said Henry was) fled the country. Whilst in France she worked tirelessly to drum up support for her husband’s cause, but not very successfully.

Eventually the chance she’d been waiting for arrived – one of the major Yorkists, the Earl of Warwick, became dissatisfied with the King he’d put on the throne. Warwick regarded himself as “Kingmaker” and felt that if this one wasn’t working out, why all he needed to do was put a new one on the throne. So he switched sides, and promised Margaret that he’d work to return her husband to his rightful throne. Margaret was quite canny about this, she accepted his aid and then waited with her son in France until Warwick had delivered on his promise. Only then did she set out for England.

Sadly for Margaret just as she and her son were landing in England the Yorkists re-grouped and retook the crown. Margaret & her forces were forced into a battle in which her son took part for the first time. He died and as he was Henry VI’s only heir, with him died the hopes of Margaret for keeping her husband’s line on the throne. Henry VI was a Yorkist captive again, and died shortly afterwards in the Tower of London. Margaret lived the rest of her life in France.

Secrets of the Arabian Nights was a standalone programme presented by Richard E. Grant all about the stories of the Arabian Nights. He traced their origins in the Middle East & beyond, and how they got to the West. He also talked to several critics & others about the impact they still have in both East & West today. And we also got treated to some retellings of some of the stories.

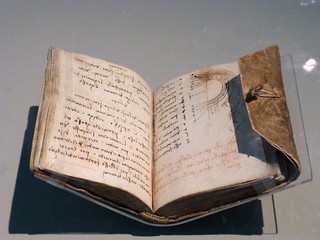

The stories come from a thriving oral tradition originating with merchants travelling the Silk Road & other trade routes across Asia. The prominence of merchants in many of the stories is a legacy of that. These stories were subsequently fitted within the Scheherazade frame story, and written down as The 1000 Stories. They came to the West via a Frenchman called Antoine Galland in the 18th Century – he was fluent in Arabic & Persian & other Middle Eastern languages, and he translated an Arabic form of the stories into French & published it. The book was a great success – partly because it was exotic and new, with sorts of stories & magic that aren’t the common tropes of Western literature (flying carpets were an example Grant mentioned repeatedly). And partly because it was the right thing at the right time – there was already a fashion for fairytales, and these stories fitted into that niche. Due to the success of the stories Galland was pressured to provide more, and he did – he said he’d heard the stories from contacts in the Middle East, but Grant pointed out that this was pretty dubious. It’s more likely that Galland invented them or significantly embellished them. I knew already that what we have in the West isn’t quite the same as the original, but I hadn’t realised that Aladdin & Ali Baba were among the extras.

Galland’s book was translated into English where again it was a success and helped establish the craze for “oriental” fashions in Britain. It was also disapproved of by the more strait-laced – Grant quote one lord who felt that it was encouraging the “Desdemona complex” (which is every bit as racist as you might imagine). And then in Victorian times the Arabian Nights stories were significantly bowdlerised & re-purposed as children’s stories. Which is really the form that most of us English speakers run into them first today.

Grant spent some time talking to a variety of critics both European & not. They were mostly in agreement that one of the themes of the book as a whole (in the original) is female sexuality & desire. They also drew out a feminist theme to the collection of stories. The framing story of Scheherazade is about a king whose wife betrays him, so after killing her he goes on to marry & then execute a woman every night. As revenge. Scheherazade uses her wits & her storytelling abilities to not just save herself but to slowly change the King’s attitudes. They were saying at the beginning the stories she tells fit with the King’s misogynistic & vengeful ideas, but over the course of the stories she emphasises wisdom & reflection over vengeance, and seeing women as people.

In the Middle East today (well, 2011 or 2010 when this was filmed) the book is controversial. It’s regarded by some as immoral – too much drinking, too much sex, people aren’t rewarded for being good they’re rewarded for being lucky, and so on. Grant talked to an Egyptian author & publisher (Gamal al Ghitani) who has published a new edition of the stories – he has received death threats & there was pressure on the government to ban the book because it was indecent & not Islamic enough. Gamal al Ghitani was clear that he felt this was rubbish, that the extremely conservative Islamist groups weren’t right about the only way to be a Muslim. And that these stories are an important part of Arabic heritage & should be read & learnt about by modern people.

It was a good programme, interesting & the dramatic re-tellings of stories were fun 🙂

Secrets of Stonehenge was a Time Team special we’d recorded several years ago, about a team excavating at and near Stonehenge. It felt very padded, in what I think of as “Discovery channel style” – i.e. the sequence went: cliff-hanger, ad break, re-cap, small bit of something else, next cliff-hanger etc. And while it did belabour the point about theories only lasting so long as there’s evidence to support them, it also made a lot of use of “and now they’ve proved” language *rolls eyes*. However. It was fun to watch, as Time Team generally is. A particularly amusing moment was when Robinson said “to help the archaeologist Time Team has built a life size replica of the henge at Durrington” … well, no, I think you did it so you had something cool to show on the telly 🙂

The excavations were led by a chap called Mike Parker Pearson, and his pet theory (which evolved over the 6 years of excavations) was that Stonehenge fit into a ritual landscape involving a progression from life to death. The henge at Durrington, built of wood, was a place where people came to feast each midwinter. They then travelled down the river Avon and along the avenue to Stonehenge, which was the place of the dead. There they buried some of their ancestors (mostly adult males, who were relatively fit – Pearson speculated this was a royal line). Some of this left me hoping it was based on better evidence than they showed us (i.e. that the people would process along the river scattering ashes?), some of it was more compelling (i.e. evidence of feasting on pigs of a particular age at the Durrington site implies feasting at a particular time of year).

Another strand of the programme talked about the previous excavations at the site – it was a minor enough theme I wouldn’t’ve mentioned it except that I wanted to make a note of one rather appalling part. One of the modern excavators, back in the 50s, was a man called Richard Atkinson. Although he did a lot of work on the site none was recorded and none was published – so effectively he dug it up & disturbed it all for no gain. Not what you expect from the modern era! Wikipedia is somewhat kinder to the man citing overwork & illness, so perhaps that too was hammed up to make “good telly”.

Overall I’d say it was fun but not necessarily accurate (or nuanced).