I’m about 3 chapters behind in writing up what I’ve read of this book – this summer has been rather busy! After the great lords Prestwich moves a step down the social scale to consider the lesser aristocracy.

The Knights and the Gentry

In contrast to the great lords (or the gentry) knights are easy to define – a knight has been through a formal process of being knighted. He gets to be addressed as “dominus” (lord), and was expected to be capable of bearing arms. Knighthood isn’t hereditary per se but the sons of knights were generally expected to become knights themselves. Generally a knight got paid more in war than a squire would (double the rate normally), he was also expected to undertake various legal and administrative duties in the country he lived in.

Despite the clear definition Prestwich says that “knights are not as easy to count as sheep”, which I found an amusing turn of phrase 🙂 Some knights are mentioned in some sources and not others, and there is no central record of who was a knight (nor even local records – when counties were asked to provide lists of knights these could vary substantially between years in ways that don’t make sense as actual changes).

The number of knights in England dropped over the first half of the 13th Century for reasons that are not entirely clear particularly as this is an era of rising population and economic prosperity (relatively speaking). There may’ve been some effect of the rising cost of military equipment, but Prestwich thinks this is not particularly significant – it correlates with rising wages for knights, but probably doesn’t cause the falling numbers of knights. As the number of knights fell the status and the duties of those left rose, as one might expect. The expectations of chivalric behaviour increased along with their role in local administration. Prestwich says there isn’t evidence of families who used to be knights resenting their loss of status – rather that there is a reluctance to take on the expense and hard work.

Later in the 13th Century life got easier for the knightly families. Prestwich associates this with the reduction in easy credit – with the Jews first less able to lend money and subsequently expelled in 1290. As well as this changes in the law meant it was harder for the Church to buy up land from knights. And other changes in the legal system meant that the duties of a knight in his county’s administration were shared with other people and so became less onerous. Prestwich also notes that a man who was knighted on the eve of battle didn’t have to pay for as elaborate a ceremony and there were several convenient battles during the later part of this period. The crown was generally concerned to ensure sufficient knights to perform the duties required of them, and at various points incentives and rewards were given to knights as part of the patronage system. There were also sometimes mass knighting ceremonies (which again would reduce costs for each individual knight).

Prestwich next moves on to the “gentry” or esquires. In the period covered by the book this social class was gradually becoming delineated, and the terms gentle born (gentiz) or gentlemen (gentis hommes) might be used. From the mid-14th Century esquire became more common as a term, too. These people can be roughly categorised as men who could be knights but weren’t – in terms of wealth and social standing it’s difficult to distinguish the groups, it’s the ceremony of knighthood that’s key. As numbers of knights dropped, and as numbers of knights who succeeded in getting exemptions from the legal & social duties rose, the numbers of esquires performing those duties increased. These include offices such as that of sheriff, coroner, forester and so on. And as well as this they served on assizes, in juries etc. At various points laws were issued to try and make sure that actual knights fulfilled the roles, but in practice it was the county elite regardless of whether or not they’d been knighted.

The county “communitas” or community can be seen as providing the essential horizontal links between the gentry & knights in society. The idea is that while ties to one’s lord or tenants provide the vertical links unifying the whole population of the country, the elite in a particular county have a sense of identity as the community of that county. Prestwich seems a bit sceptical about how important that actually was. He agrees that in terms of administration the county was very important. It was the building block for the taxation system and for the legal system. However he suggests that the way that the great lordships didn’t match up with the counties meant that the ties within the county communities were weaker than you might expect. Lists of knights for particular counties sometimes vary significantly from year to year as to whether a particular individual is part of this county or that. Knights might attend parliament as representatives of different counties in different years, rather than identifying themselves with one place & community.

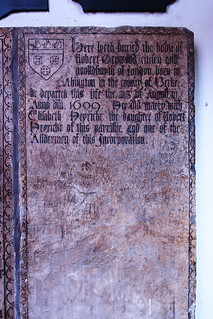

Prestwich finishes the chapter by talking about how the knights and the gentry distinguished themselves as a social elite. He calls this section “Symbols of Knighthood” which seems a bit of misnomer as it covers rather more than that. But he does open with heraldic insignia – the coat of arms was increasingly a vital signal of one’s status. The earliest surviving heraldic rolls date from the mid-13th Century and they don’t list all that many coats of arms each (e.g. 211 in Glover’s Roll, 677 in St George’s Roll from the 1280s) but across them all there are 2100 people mentioned as having coats of arms during Edward I’s reign (1272-1307) which is likely to include most or all of the knightly families. People below the rank of knight were generally not listed on the rolls, but Prestwich notes that a law in 1292 requiring esquires to use their lord’s arms suggests that some esquires were using their own. Otherwise why make a law against it. And by the 1320s there is evidence of many esquires having seals with a personal coat of arms, so they probably used them in the various other ways on clothing and so on. This again indicates the way that esquires and knights had very similar standing in society, despite the clear line between the two.

As well as coats of arms Prestwich looks at other ways that knights and esquires indicated their status. Their houses were, obviously, much less impressive than those of the earls and barons. But even tho not many have survived records indicate they often had moats or impressive looking towers – but ones that seem more for show than for defensive use. Culturally speaking the knights and esquires weren’t all that much different from their aristocratic superiors – and again it’s difficult to say much about the group as a whole, because there were many differences between individuals. Generally they were literate, educated and at least as pious as any other level of society.