Niyaz are one of the more esoteric bands that J and I listen to – fairly different from our normal rock/pop/metal staples. The core of the group is a trio of musicians who come from the Middle East originally, and play music that is based on the folk music of that part of the world – modernised, but not westernised. Their singer, Azam Ali, has one of the most gorgeous voices I’ve ever heard. Despite not understanding any of the words I enjoy listening to the music, it’s very beautiful.

We didn’t think we’d get a chance to see them play without travelling, they don’t tour extensively in Europe – Paris & Istanbul are the places we’d heard of them playing before. So when we saw there was a London gig in November we bought tickets immediately 🙂 Rich Mix is a venue we’d not been to before – in the Bethnal Green area of London, to get there we ended up walking past quite a few places that looked far too “cool” for us 😉 The venue itself was a nice space – it was a combination of a small cinema and a performance space (and a cafe). And the bar was a step up from a normal venue – much more interesting beers (I had a bottle of Asahi) and they clearly trusted the clientèle because we got real glasses and bottles, not plastic ones. The crowd weren’t quite the same sorts of people we see at the concerts we go to – a lot more women, and a lot more people who weren’t speaking English or weren’t white (or both). It made it rather obvious how non-diverse the average rock crowd is in the UK.

The concert was organised/promoted by a charity that is aiming to build artistic relationships between the Middle East & Europe (called Arts Canteen), so the concert opened with a couple of words from one of their people. There was no support band, so after that Niyaz came on and played for about an hour to an hour & a half. Most of the songs they played were from their most recent album, Sumud. The band are infectiously enthusiastic about the music they are playing and clearly were enjoying themselves, and had soon created a good atmosphere.

They didn’t speak much between songs beyond brief introductions, the exceptions were the band introductions at the end and a moment early on in the concert when Azam Ali explained some of her philosophy – that the world would be a much better place if people could concentrate more on the similarities between themselves & their neighbours and not on the differences. That peace comes first from the heart, not from the politicians. As an Iranian born woman, who spent some of her later childhood in India before emigrating to the US (and then to Canada) she has a fairly personal perspective on both the similarities between cultures and the ways that people divide & demonise the “other”.

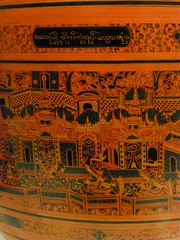

I found the visuals projected on the screen behind the band to be fascinating, but they’re not on the video I found (from the Paris show a few days before the London one), which is a shame. They were intricate line drawings of abstract patterns that were first built up then stripped back to the initial seed again. Much like the artwork for the album that we have a signed print of but animated. J didn’t notice the visuals much at all though, he was watching the musicians too much!

At the end of the concert we got a bonus encore – they invited a fan up on stage with them to play “Beni Beni” again. The fan had previously recorded herself playing along with the song on a bouzouki and the band had liked her playing so much that they’d invited her to play with them if they ever played in her town. It seemed like they hadn’t actually met or rehearsed anything with her, they just asked her to get up on stage with them at the end and then played the song – it was really good (and I really like the song so nice to hear it a second time 🙂 ).

And finally here’s a video of “Beni Beni” from the Paris gig: