For around 200 years (from the 1630s until 1858) Japan pursued a policy of isolation from the rest of the world. The Japanese people were not allowed to leave the country, and foreigners were only allowed in under very controlled circumstances. The experts who discussed it on In Our Time were Richard Bowring (University of Cambridge), Andrew Cobbing (University of Nottingham) and Rebekah Clements (University of Cambridge).

They started by putting the period of the Tokugawa Shogunate into context. 16th Century Japan could be described as chaotic – different warlords in different regions vying for power. Towards the end of that century three successive warlords tried to reunite & stabilise the country, the final one was Tokugawa Ieyasu who founded the Tokugawa Shogunate which was to rule from about 1600 until the 1860s. International relations with nearby countries at this time were strained. In part this was due to recent events – in the 1590s Toyotomi Hideyoshi tried to conquer China. To do this he invaded Korea (as it was in between China & Japan) but was beaten back by Ming Dynasty troops. Other tensions were more long standing – China saw itself as the superior country to all the surrounding ones, and trade was generally carried on via the tributary system. Japan had at times in the past been willing to play the part of a subject nation, but the Tokugawa Shogunate was not.

Relations with Europeans were also marked by tension. Prior to the onset of the Sakoku period various European nations traded with Japan, generally they brought European goods out to China to trade and they took the silk from China to Japan where they traded it for Japanese silver. With traders came missionaries – in particular Portuguese missionaries, and Jesuits. The Tokugawa Shogunate disapproved of Christianity for a couple of reasons. Firstly it encouraged people to owe allegiance to an authority that saw itself as superior to the secular authority of the Shogun (they didn’t say on the programme if they meant God or the Pope here). Secondly various of the warlords on the western side of Japan were interested in Christianity because it gave them access to trade in guns & other things that the central authority would rather they didn’t have.

So in the 1630s the third Tokugawa Shogun issued a series of edicts that began the Sakoku period. Outgoing ships were banned, people who’d moved away to other countries (as part of trade relations) were banned from coming home, Christianity was banned, the building of ocean going ships was banned and all trade from abroad had to enter through Nagasaki. Japan was able to enforce trading restrictions because the island was actually self-sufficient – the incoming trade was in luxuries. And this was looked down on, they were saying on the programme that the four classes of person in Japan at this time were samurai, farmers, artisans & merchants in that order of importance. Trade wasn’t approved of, and in particular trading for fripperies & frivolities was supposed to be beneath the dignity of a gentleman.

These edicts were enforced via threats of execution. They gave an example of an Italian missionary who tried to sneak into the country – he was caught, taken to the capital and interrogated, then buried alive. The experts also pointed out that Japan in this era was a very militarised society and people were accustomed to doing what they were told, and there was also a network of spies throughout the country to make sure disobedience was punished. And the Shogunate was seen as having brought peace & stability to the country after the chaos of the 16th Century.

Clements pointed out that this wasn’t some grand strategy. Even the name “Sakoku” is a later term. At the time these things were done as reactions to particular circumstances and then the conservatism of the Tokugawa Shogunate upheld the status quo rather than rethinking things. I guess this is “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” taken to 200-year-long extremes.

Finally external forces forced the ending of this policy of isolation. In 1854 the US Navy turned up with gunships and bullied & threatened the Japanese into letting them refuel (coal for their steam ships) and re-supply their ships to make US trade with China more easily achieved. The US Civil War distracted the Americans from finishing the job, but Britain and Russia did that – forcing Japan to sign treaties weighted in the European countries’ favour (this was normal policy when dealing with non-Western powers at that time). The Tokugawa Shogunate had been a bit rocky already when the US showed up, and collapsed soon after. After a brief civil war the Empire of Japan was formed, and within 40 years was interacting with Western powers as an equal.

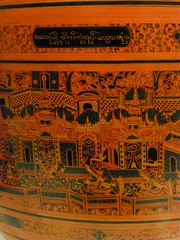

This can be seen as a very quick turn-around for Japan from isolation to embracing the modern world. But throughout the programme they were pointing out that the isolation wasn’t as complete as it’s sometimes pictured. Trade with the outside world still happened through the whole period – both with China and with the Dutch. Even though the Dutch were Christians they weren’t catholic (so no Pope) and weren’t as interested in conversion alongside trade as the Spanish & Portuguese. So they were permitted to establish a trading town on a man-made island in the harbour of Nagasaki. Another factor in their favour with the Japanese was that they were willing to go through the motions of paying tribute to the Shogun. Part of the political stance of this period was the Shogun setting itself up as another centre of a tributary system like the Chinese one.

As well as merchants all Dutch trading posts had doctors living in them – and these were the conduits of information in and out of Japan. Several wrote memoirs when they went back to Europe describing Japanese culture & history to the Europeans. And Western knowledge flowed into Japan – first medicine itself, and later other sciences like astronomy. So by the time that Japan was forced open to foreign trade there was already some knowledge of the Western world, and a literate, educated populace who could use it to learn more now that they had to.

An interesting programme about a subject I knew nothing about beyond the bare fact of its existence.