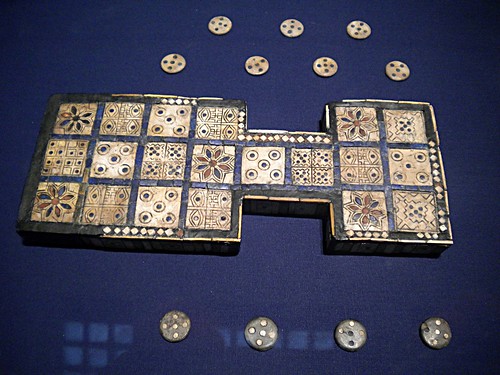

The third talk of the Bloomsbury Summer School Study Day about cuneiform was all about the Royal Game of Ur. Irving Finkel is interested in board games as well as being an expert on ancient Mesopotamian cultures and so this game is of particular interest to him. There were six boards for it found the Royal Cemetery of Ur (in southern Iraq) by Leonard Woolley. The photo below is one that I took of the board on display in the British Museum. These boards date from around 2600BC and for a long time they were the only game boards of this sort to be found. Other similar examples are now known from around the same sort of time (for example from eastern Iran, and from the Indus Valley).

The game is a race game, and the probable route is that the players start their pieces at the right hand end of the big block of squares and proceed horizontally leftwards to the rosette squares – one player at the top, one at the bottom. They then both move along the central line all the way to the right, where they separate and each follow their own track to the final rosette on the lefthand end of the small block of squares where they leave the board.

Somewhere around about the transition from the 2nd Millennium BC to the 1st Millennium BC the board changes shape. Instead of the two players separating and looping back at the end of the central run the run is extended by a further four squares. This shift in design takes place everywhere the game is played at around the same time. Finkel said this is probably because it makes the end of the game more exciting – in the original layout once you got to the split point then you probably knew you couldn’t be prevented from winning, but you still had to play out the last whatever moves before you actually won. The game spread even further with this changed layout. When the Hyksos invaded Egypt (in the Second Intermediate Period) they brought the game with them. In fact the game boxes from Tutankhamun’s grave have senet on one face and the modified Game of Ur board on the other face. Finkel took great delight in tweaking the noses of the Egyptologists in the room at this point – he pointed out that when the hieroglyphs on the sides are the right way up then the senet board is face down. So he thinks that makes it likely that the Game of Ur was the primary game not the Egyptian game of Senet!

Bringing this back to cuneiform writing Finkel discussed the first known written rules for a board game – which are on a cuneiform tablet dating to 119BC right near the end of the period that cuneiform was used. The front of the tablet has a 4×3 grid, each square of which has a zodiac sign & an inscription in. This seems to be some form of divination game – fling the dice, read off your fortune. On the reverse there are the rules for a “game fit for nobles” called the Game of Pack of Dogs. The first part of the text is a library tag written by the scribe who wrote the tablet explaining what it is and where it was copied from, the rest is the rules of the game. The rules talk about different pieces for each side, and they start in different places depending on type and on the dice roll. For instance if you roll a 5 the piece called the Storm Bird will start on square 5. There are also rules for when each type of piece lands on one of the special squares (marked with rosettes on the game board above). The rules are full of puns/jokes based on the fact that the phrase for “pack of dogs” also means “troop of soldiers”.

These are believed to be the rules for a descendent of the Royal Game of Ur, because of similarities to the only known modern survival of the game. There is a Jewish community in India who are descendants of Jews who moved there in the 1st Millennium BC from Babylon. They play a game on a board similar to the second layout for this game, using rules that are similar to the ones from the cuneiform tablet.

Finkel finished up by talking a bit about the spread & popularity of the game. He believes it was invented in the Indus Valley in the 3rd Millenium BC, and rapidly spread through the surrounding area – to Iran and then Iraq, and through India into Sri Lanka. As mentioned before the board changes in the 1st Millennium BC and this change propagates through the whole of the game playing region. It was widely played – game boards are found scratched in floors all over the region, even between the feet of the Winged Assyrian Bull gate guardians that are in the British Museum. However it was replaced almost entirely by backgammon – leaving only that one survival discussed above.